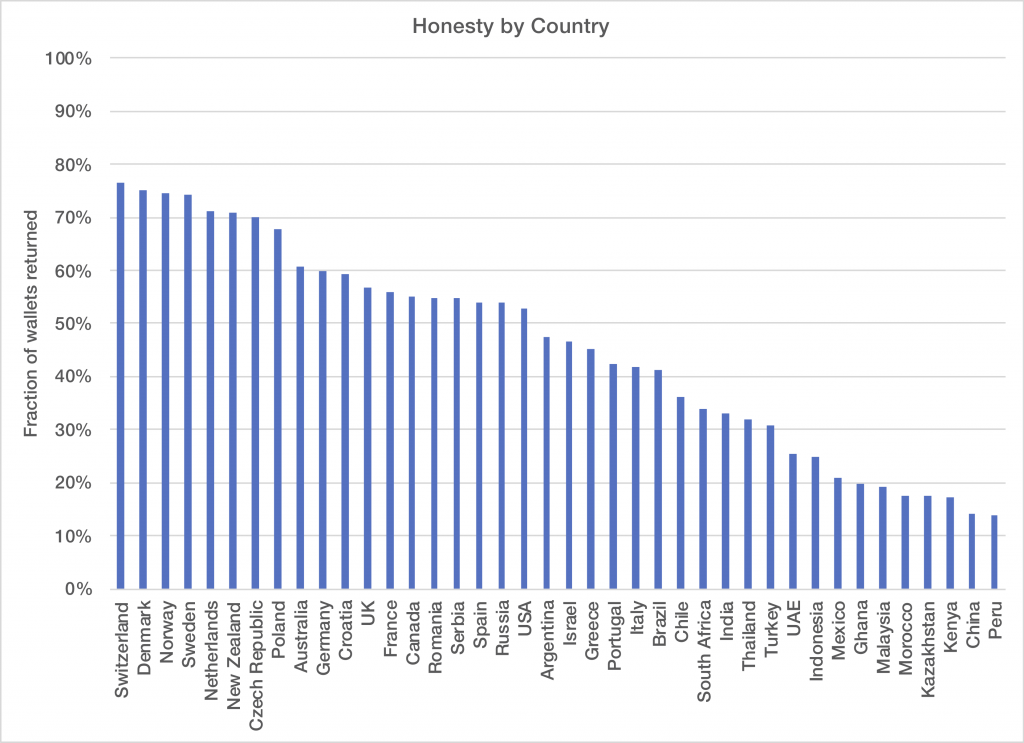

The journal Science recently published a fascinating article from Alain Cohn et al, which looked at cultural proclivities for civic honesty around the globe. They employed a rather ingenious method: they “lost” wallets all over the world and recorded when the receiver of the lost wallet attempted to return the wallet to its rightful owner. The wallets were fake and included a false ID of a person who appeared to be local to the country in which the wallet was lost, including fake contact info that actually belonged to the researchers. The ingenious element of the research was that instead of leaving the wallet out in the open, the research assistants actually pretended to have found the wallets in our nearby local businesses and turned in the wallet to somebody working in that business, thus enabling them to record interesting ancillary data on the “subject,” such as their age, if they had a computer on their desk, and whether or not the person was local to the country. Clearly, the researchers were hoping to engage in a little bit of data mining to ensure their not insignificant efforts returned some publishable results regardless of the main outcome.

As it turns out, they needn’t have been concerned. The level of civic honesty, as measured by wallet return rates, varied significantly between cultures. In addition, there is an interesting effect where the likelihood of the wallet being returned increased if there was more money in it, an effect that persists across regions and which was evidently not predicted by most economists. I encourage you to read the original article, which is fascinating. On the top end of the civic

Here’s where things get interesting: in keeping with modern scientific publishing standards, the researchers made their entire dataset available in an online data repository so that others could reproduce their work. There are a lot of interesting conclusions one can make beyond what the authors were willing to point out in their paper, perhaps due to the political implications and the difficulty of doing a proper accounting for all the possible biases. However, unburdened by the constraints of an academic career in the social sciences, I was more than happy to dig into the data to see what it could turn up…

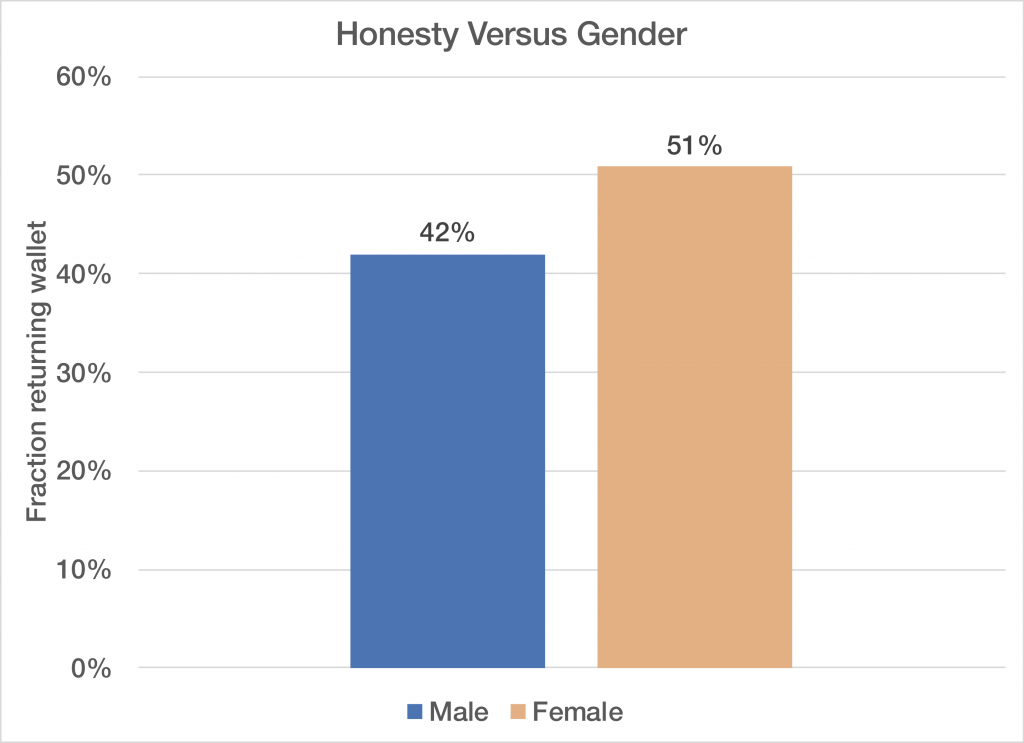

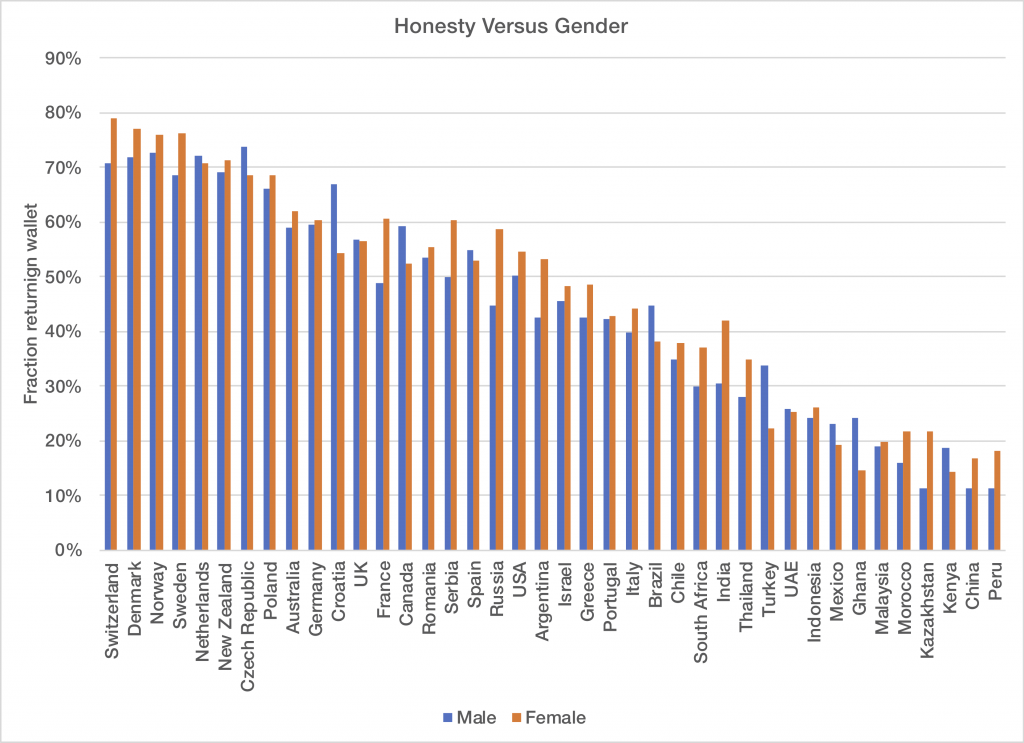

Perhaps the most interesting thing I found is that women appear to be more honest than men. Over the entire world-wide dataset, women returned the wallets about 51% of the time, versus 42% for men. It is tempting to look at individual countries, but the male versus female difference is not statistically significant enough when looking at individual countries, so I chose to only look at the aggregate data. The data is not weighted by country population, so one should take the absolute magnitude of the difference with a bit of skepticism. However, looking at the individual country data it appears a proper accounting for population bias would likely maintain or increase the difference. (Some of the most populous countries had the largest difference between women and men.)

Here is the full dataset of men versus women broken down by country. You can see that the most populous countries are those where women appear to be more honest than men, so fixing the chart above to account for sample bias would likely still find a significant difference.

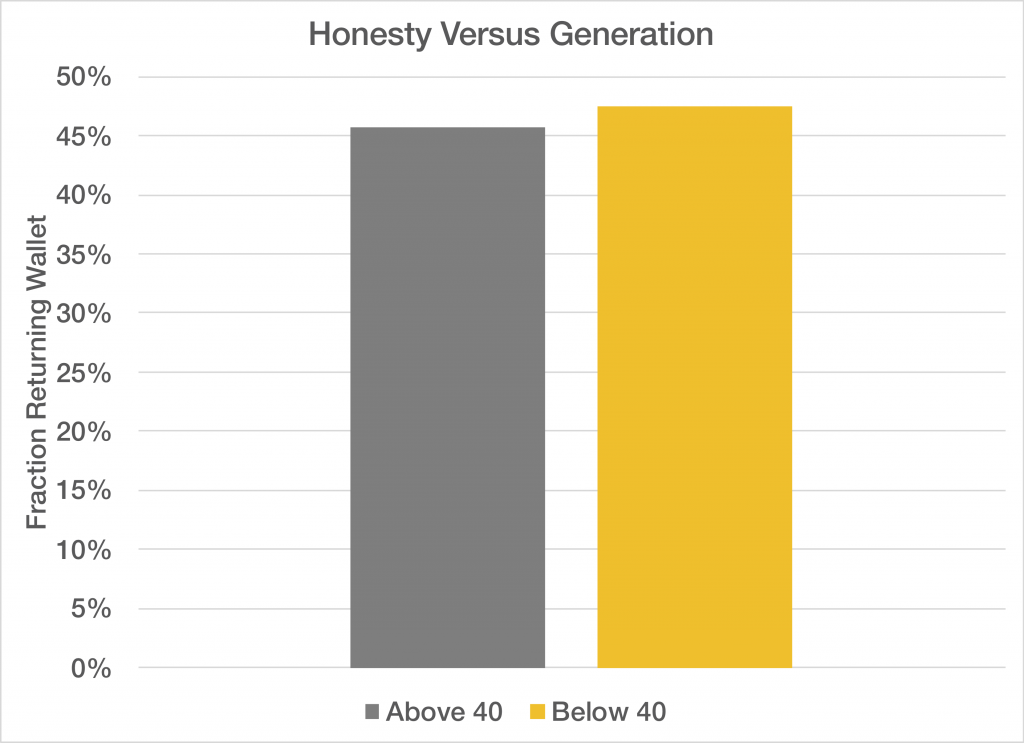

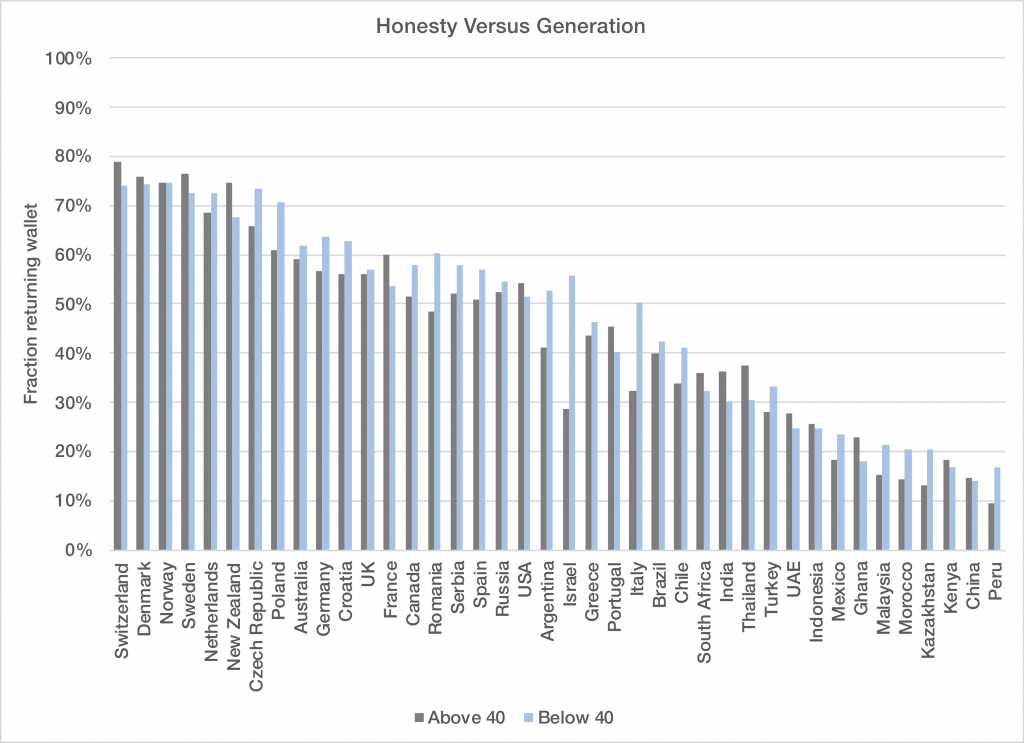

Another interesting question to ask of the data is whether or not there is a generational difference in honesty. Surprisingly, the answer turns out to be that there’s not a statistically

Looking at the breakdown by country, we see that there are no big differences between the generations, with one exception that I’m not even going to try to explain:

One interesting set of issues that always comes up with population studies like this is what, if anything, should we do with this information? It is true that a Swedish woman is about eight times more civically honest, on average, than a Chinese man. That’s interesting, but also pretty dangerous information. Should this inform our immigration policy, where population statistics might actually be valid? Is it better to not even ask these questions given the abuse of the information that might result? Or, is it good to have this information, especially when it flies in the face of our image of ourselves and others? I suspect in the case of the US, most would be surprised to find out that the average US citizen is as honest as the average Russian. We may be surprised by both halves of that statement, and both might be good to think about.