This depression is historic in many ways, but one way that doesn’t get talked about a lot is that it’s the first time America has had a credit-based downturn with a government that is a major existing factor in the economy. Before the Great Depression, in the 1920s, government spending at all levels was around 15% of personal income. Today, it’s close to 50%. Sure, government spending shot up under FDR, but the point is it shot up from virtually nothing. What happens when you hit a depression when government spending is already over one third of GDP before the depression?

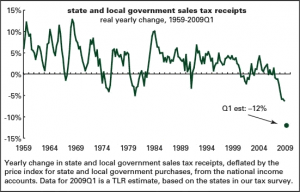

So, we have this situation where there is a huge economic entity that is about to see its income drop precipitously, as tax revenues fall off a cliff. Whether by spending cuts or inflationary printing, future real government contributions to the economy are going to have to decline. It’s easy to forget, but the government doesn’t actually make anything. Whatever money they spend either comes from the present or the future or from inflating the currency, but either way it is a hole that has to be filled sometime. Due to the large delay between the effects of a downturn and government spending, this will take a while to play out, and it’s a huge overhanging issue that has yet to completely hit the proverbial fan.

Here’s the thing that scares me about all of this: one of the tenets of control theory is that having a strong feedback loop with a large delay in any system is a good recipe for instability, and yet that’s exactly what we have when the government becomes such a large factor in the economy. Of course, an economy is not a model system, and it could never experience runaway instability like a linear circuit could. But if there are forces pushing it towards instability, I’d argue the result may not be exponentially growing oscillations, but it won’t be good. Humans don’t like unstable systems, especially when their money is involved, and rather than suffer oscillations, I suspect the economy would just fall and stay down.

Why hasn’t this happened before? Well, one likely possibility is that I’m completely out of my mind to be applying principles of control theory to the national economy. But another is that we’ve simply never tied this big of a feedback loop around our economy before. The last time we had a credit dislocation, perhaps government was small enough that these oscillations were damped. But the gain is way up, now, and I’m a little nervous to see what happens now that the system has been given a big kick.